Raku Solutions Weekly Review

Task #1: Vigenère Cipher

This is derived in part from my blog post made in answer to the Week 15 of the Perl Weekly Challenge organized by Mohammad S. Anwar as well as answers made by others to the same challenge.

The challenge reads as follows:

Write a script to implement Vigenère cipher. The script should be able encode and decode. Checkout wiki page for more information.

The Vigenère cipher is actually a misnomer: in the nineteenth century, it has been mis-attributed to French diplomat and cryptographer Blaise de Vigenère, who published the method in 1586, and this is how it acquired its present name. But the method usually associated with Vigenère’s name had been described more than three decades earlier (in 1553) by Italian cryptanalyst Giovan Battista Bellaso. It essentially resisted all attempts to break it until 1863, three centuries later. This being said, Vigenère is certainly a great figure in the history of cryptography, since he invented a very significant enhancement of that method that is not usually associated with Vigenère’s name, but is usually named autokey cypher, but that’s another story.

To understand the Vigenère cipher, we can first consider what is known as the Caesar cipher, in which each letter of the alphabet is shifted along some number of places. For example, in a Caesar cipher of shift 3, A would become D, B would become E, Y would become B and so on. So, for instance, “cheer” rotated by 7 places is “jolly” and “melon” rotated by -10 (or + 16) is “cubed”. In the movie A Space Odyssey, the ship’s computer is called HAL, which is IBM rotated by -1. One famous such cipher is ROT13, which is a Caesar cipher with rotation 13. Since 13 is half the number of letters in our alphabet, applying rotation 13 twice returns the original message, so that the same routine can be used for both encoding and decoding in rotation 13. Rotation 13 has been used very commonly on the Internet to hide potentially offensive jokes or to weakly hide the solution to a puzzle.

A Caesar cipher is very easy to break through letter frequency analysis.

In Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Gold Bug, one of the characters, William Legrand, uses letter frequencies to crack a cipher. He explains:

Now, in English, the letter which most frequently occurs is e. Afterwards, the succession runs thus: a o i d h n r s t u y c f g l m w b k p q x z. E however predominates so remarkably that an individual sentence of any length is rarely seen, in which it is not the prevailing character.

Edgar Poe’s character is slightly wrong on part of the succession of letters: for example, he grossly underestimated the frequency of letter t, which is the second most common letter in English. But what he says about letter E is correct.

So, if you want to decipher a message encoded with a Caesar cipher in English, one way is to find out the most common letter in the encoded text, and that most common letter is likely to be an E. From there, you can figure out by which value each letter has shifted and decipher the whole message. If you were unlucky, just give a try with the second most common letter, and then the third. You’re very likely to quickly succeed. Another possibility is brute force attack by trying all 26 possible values by which the letter are shifted. This is easy by hand, and very fast with a computer. A Caesar cipher is a very weak encryption system.

The idea of the Vigenère cipher is to shift each of the letters of the message by a different number of places. For example, if your encryption code is 1452, you rotate the first letter by one place, the second one by 4 places, the third by 5 places, the fourth by 2 places; if you have more letters to encode in your message, then your start again with the beginning of the code, and so on. For example, if you want to encode the word “peace,” you get:

p + 1 => q

e + 4 => i

a + 5 => f

c + 2 => e

e + 1 => f

Encoded message: qifef.

In brief, a Vigenère cipher is using a series of interwoven Caesar ciphers. With such a system, frequency analysis becomes extremely difficult because, as we can see in the example above, the letter E is encoded into I in the first instance, and into F in the second instance. In fact, if the encryption key is a series of truly random bytes and is at least as long as the message to be encoded (and is thus used only once), the code is essentially unbreakable. In practice, a Vigenère cipher is usually not using a number as encryption key, but generally a password or a pass-phrase: the letters of the password are converted to a series of numbers according to their rank in the alphabet and those numbers are used as above to rotate the letters of the message to be encoded. Since the encryption code is no longer truly random, it becomes theoretically possible to break the code, but this is still very difficult, and that’s the reason the Vigenère cipher has been considered unbreakable for about three centuries.

My Solution

For this challenge, we will use the built-in functions ord, which converts a character to a numeric code (Unicode code point), and chr which converts such numeric code back to a characters. Letters of the alphabet are encoded in alphabetic order, so that, for example, testing under the Perl 6 REPL:

> say ord('c') - ord('a');

2

because ‘c’ is the second letter after ‘a’.

Originally, I kept letters within the a..z range (folding the input message to lowercase), because the numeric codes for uppercase letters are different, in order to keep as close as possible to the original Vigenère cipher. But the original cipher was limited to this range only because of the way encoding was done manually at the time. With a computer, there is no reason to limit ourselves to such range. So, the script below use the full range of an octet (0..255), i.e. the full extended ASCII range. This way we can also encode spaces, punctuation symbols, etc. Of course, this implies that the partner uses the same alphabet and scheme.

In this script, the bulk of the work is done in the rotate-msg and rotate-one-letter subroutines. The encode and decode subroutines are only calling them with the proper arguments. And the create-code subroutine is used to transform the password into an array of numeric values.

use v6;

subset Letter of Str where .chars == 1;

sub create-code (Str $passwd) {

# Converts password to a list of numeric codes

# where 'a' corresponds to a shift of 1, etc.

return $passwd.comb(1).map: {.ord - 'a'.ord + 1}

}

sub rotate-one-letter (Letter $letter, Int $shift) {

# Converts a single letter and deals with cases

# where applying the shift would get out of range

constant $max = 255;

my $shifted = $letter.ord + $shift;

$shifted = $shifted > $max ?? $shifted - $max !!

$shifted < 0 ?? $shifted + $max !!

$shifted;

return $shifted.chr;

}

sub rotate-msg (Str $msg, @code) {

# calls rotate-one-letter for each letter of the input message

# and passes the right shift value for that letter

my $i = 0;

my $result = "";

for $msg.comb(1) -> $letter {

my $shift = @code[$i];

$result ~= rotate-one-letter $letter, $shift;

$i++;

$i = 0 if $i >= @code.elems;

}

return $result;

}

sub encode (Str $message, @key) {

rotate-msg $message, @key;

}

sub decode (Str $message, @key) {

my @back-key = map {- $_}, @key;

rotate-msg $message, @back-key;

}

multi MAIN (Str $message, Str $password) {

my @code = create-code $password;

my $ciphertext = encode $message, @code;

say "Encoded cyphertext: $ciphertext";

say "Roundtrip to decoded message: {decode $ciphertext, @code}";

}

multi MAIN ("test") {

use Test; # Minimal tests for providing an example

plan 6;

my $code = join "", create-code("abcde");

is $code, 12345, "Testing create-code";

my @c = create-code "password";

for <foo bar hello world> -> $word {

is decode( encode($word, @c), @c), $word,

"Round trip for $word";

}

my $msg = "One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind!";

my $ciphertext = encode $msg, @c;

is decode($ciphertext, @c), $msg,

"Message with spaces and punctuation";

}

In the script above, we have two MAIN multi subroutines. When the single argument is “test”, the script runs a series of basic tests (which would probably have to be expanded in a real life project); when the arguments are two strings (a message to be encoded and a password), the script runs with the input arguments.

This is an example run with the “test” argument:

$ perl6 vigenere.p6 test

1..6

ok 1 - Testing create-code

ok 2 - Round trip for foo

ok 3 - Round trip for bar

ok 4 - Round trip for hello

ok 5 - Round trip for world

ok 6 - Message with spaces and punctuation

and with two arguments:

$ perl6 vigenere.p6 AlphaBeta password

Encoded cyphertext: Qmƒ{xQwxq

Roundtrip to decoded message: AlphaBeta

In the autokey cypher improvement of the Vigenère cypher mentioned at the beginning of this post (which is the true invention made by Vigenère), the key is not repeated, but used only once, and the rest of the message is encoded using the message itself as the key. The fact that the key is no longer repeated in the coding process defeats most of the first known methods to break the traditional Vigenère cypher.

Alternate Solutions

Arne Sommer made a very simple and very concise implementation of the cypher dealing only with uppercase letters (as in Vigenère’s original cypher). His program loops on the input string’s numerical codes and at the same time on the key’s numerical codes. It adds the key’s codes when encrypting and subtract them when decrypting.

subset UCASE of Str where * ~~ /^<[A .. Z]>+$/;

unit sub MAIN (UCASE $uppercase-string, UCASE $key, :$decrypt = False);

my $base = "A".ord;

my $key-length = $key.chars;

my @string = $uppercase-string.comb.map({ $_.ord - $base });

my @key = $key.comb.map({ $_.ord - $base });

for ^@string.elems -> $p

{

my $k = $p mod $key-length;

$decrypt

?? print ($base + (@string[$p] - @key[$k] + 26) mod 26).chr

!! print ($base + (@string[$p] + @key[$k]) mod 26).chr;

}

Francis J. Whittle first wrote an ordinate helper subroutine to transform the password or the message into a list of numeric codes. Once this is done, encoding a message boils down to:

put ordinate($message).rotor(@key.elems, :partial).map({ (($_ Z+ @key) X% 26) X+ 'A'.ord})».Slip».chr.join

and decoding an encrypted message to:

put ordinate($message).rotor(@key.elems, :partial).map({ (($_ Z- @key) X% 26) X+ 'A'.ord})».Slip».chr.join

Wow, that’s quite impressive! And also a little bit cryptic: it took me quite a few minutes to understand these code lines.

Kevin Colyer also limited the input text and the key to uppercase letters, and his program also loops on the input string’s numeric codes and at the same time on the key’s numerical codes. It multiplies the key numerical codes by -1 when decrypting. His central subroutine is also fairly simple and looks as follows:

sub VigenereCipher($text,$key,$encode) {

my $offset="A".ord;

my @t = $text.uc.comb.map(*.ord-$offset);

my @k = $key .uc.comb.map(*.ord-$offset);

my @result;

my $EorD = $encode==True ?? 1 !! -1;

my $i=0;

for ^@t -> $j {

@result.push: chr($offset + ( (@t[$j]+ $EorD*@k[$i]) mod 26) );

$i=($i+1) mod @k.elems;

}

return @result.join ;

}

One little surprising thing is that Kevin decided to abort his program when the key passed to it is longer than the message. I do not see any reason to do so, quite to the contrary: the code is much more difficult to break when the key has a length equal to or larger than the message (the repeating of the key is the main weakness of the Vigenère cypher).

Athanasius wrote two helper subroutines, str2num and num2str, to convert a string into an array of numerical items and back, which can be used both for the input string and the key. Before starting to encode or decode, the program copies the key numeric codes as many times as needed to obtain a final key equal to or longer than the text. At this point, encrypting a message from the array of its numeric codes becomes fairly easy:

while @plain

{

my $m = @plain.shift;

my $k = @key.shift;`

@cipher.push: ($m + $k) % @ALPHABET.elems;

}

return num2str(@cipher);

}

and decrypting is just about the same with a minus sign instead of a plus.

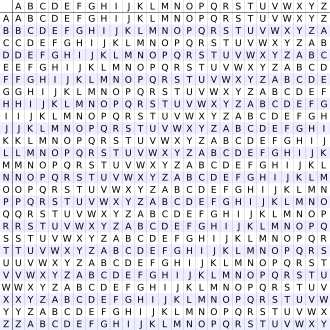

Jaldhar H. Vyas chose an unexpected and uncommon approach: he actually wrote a tabula recta:

i.e. Vigenère’s original table of alphabets written out 26 times, each time shifted by one letter, in the form of hash of strings: A => ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ, B => BCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZA, .... Once this preparation work is done, this encrypt subroutine becomes quite concise:

sub encrypt(@key, $keylength, %tabulaRecta, $c) {

state $i = 0;

return substr(%tabulaRecta{@key[$i++ % $keylength]}, ord($c) - ord('A'), 1);

}

Joelle Maslak decided to accept upper case and lower case alphabetical characters for the input message. She managed the array of letters representing the key as a circular buffer: at each step during encoding or decoding, her program moves the first letter of the key to the end of the array, so that, for coding or decoding a message, her program always picks up the letter of the array.

Ruben Westerberg decided to use an alphabet containing upper case and lower case ASCII letters plus spaces and a few punctuation symbols. His program reads line by line from a file and writes to a file. It uses heavily the >> hyper-operator to encode in just one statement the input array of integer ASCII codes into an array of encoded numbers. I must say that it took me a while to understand that statement.

sub MAIN ( Str $key, Bool :$decode, Str :$file ) {

my $f=$decode??1!!-1;

$*OUT.out-buffer=0;

my @alpha=("a".."z","A".."Z"," ", <? ! . : >)[*;*];

my @a=@alpha.keys;

my @k=$key.comb.map(-> $c {|@alpha.grep($c,:k)});

for $*IN.lines -> $line {

my @in= $line.comb.map(->$c {|@alpha.grep($c,:k)});

my @t= (@in >>+>> (@k >>*>> $f)) >>%>> @a.elems;

put join "", @alpha[@t];

}

}

Task #2: Strong and Weak Prime Numbers

This is derived in part from my blog post1 and blog post2 made in answer to the Week 15 of the Perl Weekly Challenge organized by Mohammad S. Anwar as well as answers made by others to the same challenge.

The challenge reads as follows:

Write a script to generate first 10 strong and weak prime numbers.

For example, the nth prime number is represented by p(n).

p(1) = 2

p(2) = 3

p(3) = 5

p(4) = 7

p(5) = 11

Strong Prime number p(n) when p(n) > [ p(n-1) + p(n+1) ] / 2

Weak Prime number p(n) when p(n) < [ p(n-1) + p(n+1) ] / 2

A strong prime is a prime number that is greater than the arithmetic mean of the nearest primes above and below (in other words, it’s closer to the following than to the preceding prime). A weak prime is a prime number that is less than the arithmetic mean of the nearest prime above and below. Obviously, a prime number cannot both strong and weak, but some prime numbers, such as 5 or 53 (we’ll see more of them later), are neither strong, nor weak (they’re called balanced primes): for example, 5 is equal to the arithmetic mean of 3 and 7. Therefore, the fact that a prime is not strong doesn’t mean that it is weak.

My Solutions

First Steps

We don’t know in advance how many prime numbers we’ll need to check to find 10 strong and 10 weak primes. This is a typical situation where using Perl 6’s infinite lazy lists is very convenient.

In the first code example below, we first build a lazy infinite list of prime numbers, and then use grep to filter the strong (and weak) primes, so as to construct lazy infinite lists of strong and weak primes, and we finally print out the first 10 numbers of each such list. This is fairly straight forward:

use v6;

my @p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; #Lazy infinite list of primes

my @strong = map { @p[$_] },

grep { @p[$_] > (@p[$_ - 1] + @p[$_ + 1]) / 2 }, 1..*;

my @weak = map { @p[$_] },

grep { @p[$_] < (@p[$_ - 1] + @p[$_ + 1]) / 2 }, 1..*;

say "Strong primes: @strong[0..9]";

say "Weak primes: @weak[0..9]";

This script displays the following output:

$ perl6 strong_primes.p6

Strong primes: 11 17 29 37 41 59 67 71 79 97

Weak primes: 3 7 13 19 23 31 43 47 61 73

We don’t really need to build the intermediate @strong and @weak lazy infinite lists, but can print out the results directly:

use v6;

my @p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; # Lazy infinite list of primes

say "Strong primes: ", (map { @p[$_] },

grep { @p[$_] > (@p[$_ - 1] + @p[$_ + 1]) / 2 }, 1..*)[0..9];

say "Weak primes: ", (map { @p[$_] },

grep { @p[$_] < (@p[$_ - 1] + @p[$_ + 1]) / 2 }, 1..*)[0..9];

This prints out the same lists as before:

perl6 strong_primes.p6

Strong primes: (11 17 29 37 41 59 67 71 79 97)

Weak primes: (3 7 13 19 23 31 43 47 61 73)

We’re now down to three code lines instead of five (except that I have to format each of the two last code lines over two typographical lines to fit cleanly on my editor screen or on this blog post).

Categorizing or Classifying Primes

One slight problem with the implementation above is that, once we have generated our list of primes, we need to go through it twice with the map ... grep chained statements, one for the strong primes and once for the weak primes; and we’d need to visit the prime list a third time for finding balanced primes. Although the script runs very fast, it would be better if we could do the categorizing in one go. Perl 6 has two built-in routines to do that, categorize and classify. Let’s try to use the first one:

use v6;

my @p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; # Lazy infinite list of primes

sub mapper(UInt $i) {

@p[$i] > (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 ?? 'Strong' !!

@p[$i] < (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 ?? 'Weak' !!

'Balanced';

}

my %categories = categorize &mapper, 1..120;

for sort keys %categories -> $key {

say "$key primes: ", map {@p[$_]}, %categories{$key}[0..9];

}

Running this program produces the following output:

$ perl6 strong_primes.p6

Balanced primes: (5 53 157 173 211 257 263 373 563 593)

Strong primes: (11 17 29 37 41 59 67 71 79 97)

Weak primes: (3 7 13 19 23 31 43 47 61 73)

Here, we define a mapper subroutine to find out whether a given prime is strong, weak or balanced. Then, we pass to categorize two arguments: the mappersubroutine and a range of subsequent integers (the indexes of the @p prime number list) starting with 1 (the first prime cannot be weak or strong or balanced, since it has no predecessor) and store the result in the %categories hash, which is in fact a hash of arrays with three keys (one for each type of primes) and values being the index in the @p prime array of primes belonging to the corresponding type.

For example, with an input range of 1..30, the %categories hash has the following contents:

{

Balanced => [2 15],

Strong => [4 6 9 11 12 16 18 19 21 24 25 27 30],

Weak => [1 3 5 7 8 10 13 14 17 20 22 23 26 28 29]

}

Remember that the numbers in the three lists above are obviously not the primes, but the indexes of the primes in the @p array.

Then, the for loop extracts 10 numbers from each key of hash (with a full input range of 1..120).

This categorize built-in is very useful and practical for cases where you want to split some input data into different categories, but it isn’t well adapted to our case in point, because it does not work with lazy lists. And since balanced primes are much less common than strong and weak primes, I was forced to use a relatively large range of 1..120 to make sure that I would get 10 balanced primes. For this specific problem, the classify built-in subroutine works essentially as categorize and also reports the Cannot classify a lazy list error message when trying to use it on a lazy infinite list. The difference between categorize and classify is that the latter returns a scalar whereas the former can return a list; so, in our example, it might have been slightly better to use classify rather than categorize, but the difference between the two built-ins is insignificant in our case.

We will come back to this later.

Using Functional Programming

I want to use the opportunity of this challenge to illustrate once more some possibilities of functional programming in Perl

In fact, the first solution suggested above is in fact already largely functional in spirit. We’re using a data pipeline programming model. The code lines with map and grep statements should be read from bottom to top (when they are formatted over more than one line) and from right to left. For example, to understand this code line:

my @strong = map $p[$_],

grep { $p[$_] - $p[$_-1] > $p[$_+1] - $p[$_] } 1..25;

one needs to start from the 1..25 range, which is fed to the grep statement, whose role is to filter the range values and keep those which satisfy the condition within the grep block. This means, in this case, to keep the indexes of values in the @p array of prime numbers for which the current prime number is closer to the next prime than to the previous prime. These indexes are then fed to the map statement in order to populate the @strong array with such primes.

This implementation works fine, but we saw that there is a weakness: we’re scanning the @p array of prime numbers twice (or even three times if we want to also identify the balanced primes). And the other solution using categorize or classify removed that weakness, but was not entirely satisfactory because we could no longer use lazy infinite lists for our input values.

Note that these weaknesses don’t matter very much, since we’re dealing with small ranges anyway, but that’s not really satisfactory to the mind, as we know that these programs wouldn’t scale too well for larger ranges. Let’s see whether we can improve these programs.

I hate to say that, but an easy solution is to write a non (or less) functional solution using an infinite loop.

For example, this could be something like this:

use v6;

my @p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; # Lazy infinite list of primes

my (@strong, @weak, @balanced);

for 1..* -> $i {

if @p[$i] > (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 {

push @strong, @p[$i];

}

elsif @p[$i] < (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 {

push @weak, @p[$i];

} else {

push @balanced, @p[$i];

}

last if @balanced.elems >= 10;

}

say "Strong primes: @strong[0..9]";

say "Weak primes: @weak[0..9]";

say "Balanced primes: @balanced[]";

This script produces the following output:

$ perl6 strong_primes.p6

Strong primes: 11 17 29 37 41 59 67 71 79 97

Weak primes: 3 7 13 19 23 31 43 47 61 73

Balanced primes: 5 53 157 173 211 257 263 373 563 593

Note that in the code above, we use the fact that we know from previous tests that balanced primes are much less frequent than either strong or weak primes, so that we can stop the for loop when we have 10 balanced primes (if we did not know that, we would have had to test the three arrays) . Also note that this works fine because, in Perl 6, a for loop is lazy. There may be some possible minor improvements, for example avoiding multiple dereferencing of the @p values, but I’m not really interested here with micro-optimizations.

This new version works fine, but that’s really not the way I would like to go: I would like to have a more functional version , not a less functional version.

Let’s come back to the categorize and classify built-in functions. As already noted, they’re perfect for what we want to do, but don’t work with infinite lists.

Let’s see if we can write our own version of categorize or classify which would have the same calling syntax and be able to handle infinite lists. Our version of this function will be called distribute.

@p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; # Lazy infinite list of primes

sub mapper(UInt $i) {

@p[$i] > (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 ?? 'Strong' !!

@p[$i] < (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 ?? 'Weak' !!

'Balanced';

}

sub distribute (&code, @primes) {

my %distribution;

for @primes.kv -> $key, $val {

next if $key == 0;

push %distribution{&code($key)}, $val;

last if %distribution{'Balanced'}.elems >= 10;

}

return %distribution;

}

my %categories = distribute &mapper, @p;

for sort keys %categories -> $key {

say "$key primes: ", %categories{$key}[0..9];

}

Note that, contrary to the previous version, the %distribution and %categories hashes now contain the primes, not the prime indexes in the prime array.

And we no longer need to estimate the number of input values to get the desired output.

I am not fully satisfied, though, because our distribute subroutine is tailored to our problem at hand and is not generic enough:

- We need to skip (

next if ...) the first prime of the list , because it is neither strong, nor weak, nor balanced, since it has no predecessor (and we would get an out-of-range index error or something similar if we kept it); we can solve that by tagging the first index (0) as'Excluded'in themappersubroutine, and by excluding that new category from the final output. - The stopping condition (

last if ...) is hard-coded in thedistributesubroutine. Well, we can pass todistributea third argument, another code block ($stopper), to stop the iteration.

These two changes will make our distribute subroutine more generic:

use v6;

my @p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; # Lazy infinite list of primes

sub mapper(UInt $i) {

$i < 1 ?? 'Excluded' !!

@p[$i] > (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 ?? 'Strong' !!

@p[$i] < (@p[$i - 1] + @p[$i + 1])/2 ?? 'Weak' !!

'Balanced';

}

sub distribute (&code, @primes, &stopper) {

my %distribution;

for @primes.kv -> $key, $val {

push %distribution{&code($key)}, $val;

&stopper(%distribution);

}

return %distribution;

}

my $stopper = { last if %^a{'Balanced'}.elems >= 10 };

my %categories = distribute &mapper, @p, $stopper;

for sort keys %categories -> $key {

next if $key eq 'Excluded';

say "$key primes: ", %categories{$key}[0..9];

}

The only trick here if that the $stopper code block uses a self-declared positional parameter (or placeholder), %^a. And we pass the %distribution hash as a parameter to &stopper when we run it within the distribute subroutine. Thus, the calling code doesn’t have to know the name of the hash within the distribute subroutine, which is now generic. To be frank, I wasn’t fully convinced that this would work until I ran it.

The output is what we want:

$ perl6 strong_primes.p6

Balanced primes: (5 53 157 173 211 257 263 373 563 593)

Strong primes: (11 17 29 37 41 59 67 71 79 97)

Weak primes: (3 7 13 19 23 31 43 47 61 73)

A final comment on all this. I called distribute my new version of the classify or categorize subroutines because I did not want to mess around the semantics of those existing functions. But it works to define the distribute subroutine as a multi sub classify subroutine:

use v6;

my @p = grep { .is-prime }, 1..*; # Lazy infinite list of primes

sub mapper(UInt $i) {

# same code as just above

}

multi sub classify (&code, @a, &stopper) {

my %distribution;

for @a.kv -> $key, $val {

push %distribution{&code($key)}, $val;

&stopper(%distribution);

}

return %distribution;

}

my $stopper = { last if %^a{'Balanced'}.elems >= 10 };

my %categories = classify &mapper, @p, $stopper;

for sort keys %categories -> $key {

next if $key eq 'Excluded';

say "$key primes: ", %categories{$key}[0..9];

}

I no longer get the Cannot classify a lazy list error message, this code works fine and it outputs the same result as before. This was just to test that this could be done syntactically and would work, but I wouldn’t want to do that in actual production code without first very closely looking at the semantics of the built-in classify subroutine: I do not want to create a monster with a different meanings depending on the circumstances.

Alternative Solutions

Arne Sommer first generated a lazy infinite list of prime numbers. Then, his program iterates over successive integers and, for each such integer, determines whether the prime having that index in the prime array is strong or weak (or neither), and pushes those in the right array. The loop stops when both the @strong and @weak arrays have at least 10 elements. It then prints 10 elements of each array.

It is worth noting that Arne used a sigil-less variable, p, for his array of primes, as well as for his for loop iteration variable (n), so that his code to compute whether a prime is strong or weak looks almost exactly the same as the math formulas of the challenge specification:

if p[n] > ( p[n-1] + p[n+1] ) / 2 { # ...

That’s quite a nice feature, because the code can be understood and possibly even checked (to a certain degree) by domain experts, not just software engineers or CS scientists (even though, or course, we’re talking here about rather trivial examples).

Athanasius used a next-prime subroutine that acts essentially as an iterator: each time it is called, it returns a new prime number (keeping track of the last one that was provided). Otherwise, his program maintains a hash of 2 arrays (strong and weak primes). Then, while we don’t have enough primes of each category, the program calls next-prime to get another prime ($next) and stores into one of the categories, if it meets the criteria. The program also maintains a $previous prime and a current prime to be able to perform the proper comparisons.

Jaldhar M. Vyas created first a lazy infinite list of primes, and then use a grep to create a lazy infinite list of strong primes and a lazy infinite list of weak primes, and finally printed the first ten items of each of those two last lists. Essentially the same thing as my first solution, except that Jaldhar’s program is using chained method invocations (where mine uses chained function calls). Here is the example for the strong primes:

my @strongPrimes = (1 .. ∞)

.grep({ @primes[$_] > (@primes[$_ - 1] + @primes[$_ + 1]) / 2 })

.map({ @primes[$_] });

Joelle Maslak also created a lazy infinite list of primes. Then, she created the lists of strong and weak primes using a lazy gather/take block. For example for the strong primes:

my @strong = lazy gather {

for 1..∞ -> $i {

take @primes[$i] if @primes[$i] > @primes[$i-1,$i+1].sum / 2

};

}

Ruben Westerberg also created a lazy infinite list of primes. Then, while iterating over successive integers, his program populates a kind of circular buffer (@ps) of three primes and does the required computations on this circular buffer. This works, but seems a bit contrived to me: why not making directly the computations on the previous, current and next elements of the @primes array, since we have an index that can be used on that array?

SEE ALSO

Only two blog posts on the strong and weak primes, as far as can say:

- Arne Sommer: https://perl6.eu/prime-vigenere.html.

- Jaldhar M. Vyas: https://www.braincells.com/perl/2019/07/perl_weekly_challenge_week_15.html. As of this reading (Aug. 2019), Jaldhar’s post has a small Unicode rendering problem in a sentence on ironically the Unicode subject: “(By the way, I love how you can use unicode symbols as syntax in Perl6. But if your editor can’t cope, you can use * instead of ∞.)” Jaldhar is speaking about the

∞infinity symbol. The same problem occurs in the relevant code sample of the blog post. This being said, note that the ∞ symbol is rendered correctly in his code samples on Github, it is only in the blog post that there is a problem.

Three blog posts on the Vigenère Cypher:

-

Arne Sommer: https://perl6.eu/prime-vigenere.html.

-

Jaldhar M. Vyas: https://www.braincells.com/perl/2019/07/perl_weekly_challenge_week_15.html.

-

Damian Conway: http://blogs.perl.org/users/damian_conway/2019/07/vigenere-vs-vigenere.html. This blog post is truly awesome, as usual, you should really follow the link.

Wrapping up

Please let me know if I forgot any of the challengers or if you think my explanation of your code misses something important.

If you want to participate to the Perl Weekly Challenge, please connect to this site.